The Sacraments

In the Catechism in the 1979 Book of Common Prayer, we read that the sacraments are “outward and visible signs of inward and spiritual grace, given by Christ as sure and certain means by which we receive that grace” (BCP, p. 857). Grace is defined in the Catechism as “God’s favor toward us, unearned and undeserved; by grace God forgives our sins, enlightens our minds, stirs our hearts, and strengthens our wills” (BCP, p. 858). The two great sacraments of the Gospel given by Christ to his Church are Holy Baptism and the Holy Eucharist (BCP, p. 858).

Holy Baptism

John the Baptist baptized in water but announced also the coming of a “Strong One” who would baptize with the Holy Spirit (Mk 1:7-8). John focused primarily on the need for repentance and the importance of the future (eschatology). The early Christian community saw the fulfillment of John’s promise in the Pentecost event (Acts 1:5). The gift of the Spirit was extended to converts through the response of faith, followed by baptism in the name of Jesus (Acts 2:38). While the reception of the Spirit is invariably associated with baptism, it occasionally precedes (Acts 10:44-48) or follows (Acts 8:14-17; 19:2-9) baptism. The Episcopal Church maintains that “Holy Baptism is full initiation by water and the Holy Spirit” into the church (BCP, p. 298). The Episcopal Church thus recognizes no baptism in or of the Spirit separate from or additional to sacramental initiation.

Baptism is full initiation by water and the Holy Spirit into Christ’s Body, the church. God establishes an indissoluble bond with each person in baptism. God adopts us, making us members of the church and inheritors of the Kingdom of God (BCP, pp. 298, 858). In baptism we are made sharers in the new life of the Holy Spirit and the forgiveness of sins. Baptism is the foundation for all future church participation and ministry. Each candidate for baptism in the Episcopal Church is to be sponsored by one or more baptized persons. Sponsors (godparents) speak on behalf of candidates for baptism who are infants or younger children and cannot speak for themselves at the Presentation and Examination of the Candidates.During the baptismal rite the members of the congregation promise to do all they can to support the candidates for baptism in their life in Christ. They join with the candidates by renewing the baptismal covenant. The water of baptism may be administered by immersion or affusion (pouring) (BCP, p. 307). Candidates are baptized “in the Name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit,” and then marked on the forehead with the sign of the cross. Chrism may be used for this marking. The newly baptized is “sealed by the Holy Spirit in Baptism and marked as Christ’s own for ever.” When all baptisms have been completed, the celebrant and congregation welcome the newly baptized into the household of God.Baptism is normally administered within the Eucharist as the chief service on a Sunday or another feast. The Catechism notes that “Infants are baptized so that they can share citizenship in the Covenant, membership in Christ, and redemption by God.” The baptismal promises are made for infants by their parents and sponsors, “who guarantee that the infants will be brought up within the Church, to know Christ and be able to follow him” (BCP, pp. 858-859). Baptism is especially appropriate at the Easter Vigil, the Day of Pentecost, All Saints’ Day or the Sunday following, and the Feast of the Baptism of our Lord (the First Sunday after the Epiphany). These feasts of the church year may be referred to as baptismal feasts. As far as possible, baptism should be reserved for these feasts or occasions or when a bishop is present (BCP, p. 312).

The Holy Eucharist

God said to the Israelite community, “You shall be holy, for I, the LORD your God, am holy” (Leviticus 19:2). The holiness commanded in the Hebrew Scriptures is external, or ceremonial, as well as internal, or moral and spiritual. The word eucharist means “thanksgiving” in Greek. Externally and internally, giving thanks is a holy act. The genesis of the Christian Eucharist is found in the Jewish ritual of gathering habitually for prayerful meals of thanksgiving. Following Jesus Christ’s death and resurrection, prayers and particular acts of eating were formalized into a Christian liturgical service. The service of the Holy Eucharist as we know it today was customary by the early third century A.D. The primary act of Christian worship during which we receive the sacrament of Jesus Christ’s body and blood, the service of Holy Eucharist is a common sacrifice and common meal shared by the Christian community. The Eucharist was given by Christ as a means for receiving God’s grace. Grace is God’s unearned and undeserved favor towards us. By grace, “God forgives our sins, stirs our hearts, enlightens our minds, and strengthens our wills” (BCP, p. 858).

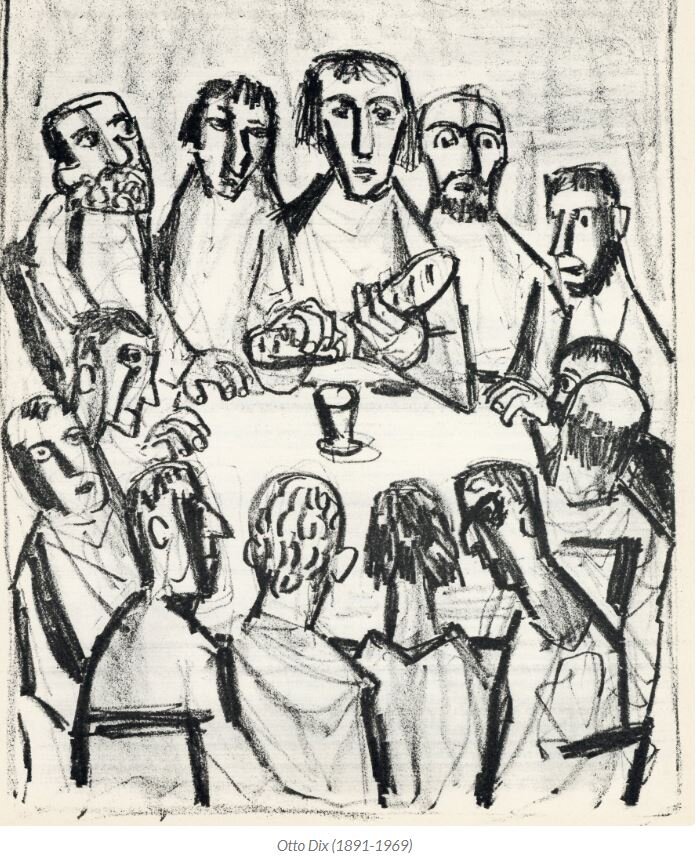

Jesus often shared sacred meals with his followers. He and his followers shared a meal immediately preceding his betrayal and arrest. While sharing bread and wine at a sacred meal with his followers, Jesus instituted the Eucharist during the Last Supper on the night he was betrayed. Christ’s sacrifice is made present by the Eucharist and in it Christians are united to his self-offering. The Last Supper established the Eucharistic action of taking, blessing, breaking, and sharing. Christ’s body and blood are present in the sacrament of the Eucharist and received by faith. Christ’s presence is also known in the gathered Eucharistic community. Jesus identified the bread with his body and the wine with his blood of the new covenant. He instructed his followers to continue to do this in remembrance of him (1 Corinthians 11:23-26; Mark 14:22-25; Matthew 26:26-29; Luke 22:14-20).

The new covenant is the new relationship with God given by Jesus Christ to his early followers and through them to all of us. Christ promises to bring us into the kingdom of God and to share the fullness of life with us. We respond by believing in Christ and keeping his commandments. Jesus taught the summary of the law and the new commandment. The summary of the law is that we are to love God with all our hearts, souls, and minds, and we are to love our neighbor as ourselves. The new commandment is that we are to love one another as Christ loved us.

The Holy Eucharist was called “The Supper of the Lorde and the Holy Communion, commonly called the Masse” in the first English language Prayer Book of 1549. Today, the Holy Eucharist contains two parts. The first part of the service is the Proclamation of the Word of God. It normally includes lessons from Holy Scriptures, a sermon, the Nicene Creed, prayers of the people, and the confession of sin and absolution. The first part of the service concludes with the peace, which is a liturgical exchange of greeting through word and gesture. The peace is a sign of reconciliation, love, and renewed relationships in the Christian community. The Celebration of the Holy Communion is the second part of the service. The first action of the Celebration of the Holy Communion is the offertory, in which bread and wine along with money and other gifts are presented to a deacon or priest who then sets the altar for the feast. The Celebration of Holy Communion continues with the consecration of bread and wine, the Lord’s Prayer, the communion of the people, and the concluding prayers of thanksgiving and dismissal. From the dismissal, we get the name Mass, by which the service of Holy Eucharist is also known. During the dismissal in the medieval Mass, the people were told “Ite, missa est,” which means “Go, it is finished” in Latin.

While they were eating, Jesus took a loaf of bread, and after blessing it he broke it, gave it to the disciples, and said, “Take, eat; this is my body.” Then he took a cup, and after giving thanks he gave it to them, saying, “Drink from it, all of you; for this is my blood of the covenant, which is poured out for many for the forgiveness of sins.” - Matthew 26: 26-27